System

Passing down Traditional Technology

Passing down the Secrets of Technology to Only One Successor

During the Edo Period (1603 - 1868), important technologies were primarily handed down from the father to the eldest son, or sometimes from the master to his first disciple. This system is indicated by old documents that list the chief carpenters’ names. During the Edo Period, the Kintaikyo Bridge projects were implemented by the Iwakuni Domain. Carpenters engaged in the projects were vassals of the lord of Iwakuni. Among the vassals, those who belonged to a specific family succeeded to the role of bridge construction. Accordingly, the bridge building technology was inherited in that family. In handing down technologies, it is essential that successors have first-hand experience. Regarding the technologies involved in building wooden structures, there are aspects that even the best drawing or book cannot record. Without experiencing actual bridge construction, no carpenter can build a wooden bridge like the Kintaikyo.

Historic Materials

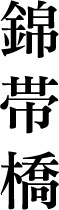

Many historic documents remain regarding the Kintaikyo Bridge. Of them, the oldest extant material is the drawing prepared in 1699 (Fig. 2). (There are 12 additional drawings that remain intact today.) The oldest drawing indicates in detail the types, dimensions and production centers of the timbers used for the Bridge; types and number of necessary metal fittings; primary dimensions and gradients of beams used for the three arches in the Bridge’s central portion etc. Without these documents, it would have been impossible to rebuild the Bridge each time it was carried away.

To long sustain the bridge building technology, we must also prepare and preserve such records for future generations.

|

| Fig. 2: The oldest extant drawing of the bridge, prepared at the time of rebuilding in 1699 |

To Learn from Wood to Know Wood

|

| Photo 10: Marking on timbers |

Since the Edo Period, carpenters have passed down verbally the secrets of their technology, or aspects that are difficult to express either in text or drawing. Among such secrets is the method of learning from wood the nature inherent in each respective wood type. Each timber has a different and unique nature, which can be learned only by viewing and touching the timber, and using all five senses. Without knowing the nature of each timber, carpenters cannot use it for the appropriate purpose (Photo 10).

Unfortunately, the wide spread of laminated lumber provides contemporary carpenters with few opportunities to learn from wood. In this environment, rebuilding the Kintaikyo Bridge, which employs authentic timbers, is a golden opportunity for carpenters to acquire the skill of learning from wood the nature inherent in each type of wood.

Establishing a New Order Placement System

The Order System Prioritizing Technological Transfer

Since the construction of the first bridge, the Kintaikyo has been rebuilt and maintained by local people. To long sustain the traditional bridge building technology, it is best that such technology be passed down to local people. With this view, in selecting builders the local authority adopts a single tendering method rather than a competitive tender, which is the most common way of ordering public works. Although use of the single tendering method is rare, in the case of the Kintaikyo projects it is most effective in transferring traditional technology.

A drawback of the single tendering method, however, is that project expenses can become higher due to the lack of competitive bidding. Even so, this system is essential for passing down traditional technologies to future generations in the Iwakuni region, as well as for maintaining local carpenters’ enthusiasm for inheriting their predecessors’ high technical expertise.

Order Placement by Type of Work

Rebuilding the Kintaikyo Bridge requires various types of work, including temporary structure construction (building footings etc.), civil engineering (preparing work yard), carpentry (timber processing and bridge building), metal processing (processing steel and copper plates), painting (painting timbers and steel members for antiseptic treatment), procurement (purchase of timber) and nail production (producing traditional Japanese nails). Since from the standpoint of managerial efficiency it is unwise to place separate orders for individual types of work, in the recent project the local authority placed orders - orders for temporary structure construction, civil engineering, carpentry, metal processing and painting - collectively with a local builders’ union. However, the authority placed orders with timber merchants and nail producers on an individual basis. Instead of supplying raw materials to individual worker unions, the authority supplied them to the principal contractor, i.e. the local builders’ union. As to carpentry work, the primary contractor subcontracted the work to a local carpenters’ union. Since carpenters usually work by themselves, the primary contractor subcontracted the project, involving hundreds of millions of yen, to the carpenters’ union rather than to individual carpenters. Similarly, the primary contractor subcontracted other types of work to selected local unions, rather than to individual workers. Since this method has been effective in passing down traditional techniques to younger generations, the authority will continue this order placement system in the future.

To Pass on Building Technology to Future Generations

Fostering Carpenters

Only carpenters who have received sufficient training can process timbers and build a bridge like the Kintaikyo Bridge. To build a structure using traditional technology, carpenters must have expertise in processing timbers, as well as skills in identifying the inherent nature of individual timbers.

Recently, however, carpenters primarily use precut, laminated timbers. Contemporary carpenters therefore have fewer opportunities to use and process authentic, live timbers. Therefore, rebuilding the Kintaikyo Bridge affords carpenters a rare opportunity to learn the traditional technology of wood building. In the rebuilding project conducted during the Heisei Period (1989 -), carpenters of various generations were recruited to take part in the project, so as to transfer timber processing and bridge building technologies to younger generations. To foster future carpenters, the workers who were engaged in the most recent project are currently organizing various training programs, including seminars. The City of Iwakuni believes that such programs are essential for handing down the traditional technology to future generations. With this view, the City is considering establishing an appropriate system to support such activities.

Timber Production System

During the Edo Period, the Bridge was built using locally available timber. In recent projects, however, including the one during the Heisei Period (1989 -), rebuilding projects had to rely primarily on a supply of timber from other prefectures. There are various, rigorous requirements for the wood materials to be used in building the Bridge, since they must withstand extremely severe climatic and weather conditions. Only timbers of large diameter can meet these requirements. In the local mountains and forests owned by the City of Iwakuni, however, no such trees were found.

The City of Iwakuni therefore has designated a special forest to grow wood for use in future Kintaikyo Bridge rebuilding projects. Since the trees planted in the forest are still young - about 80 years old -, they cannot be used now. They should be preserved, however, for use in future. To pass down the traditional bridge building technology to future generations, some suggested that the Bridge be rebuilt every twenty years. In line with this proposal, the authority has designated a new forest, where seedlings will be planted in March 2008 to prepare timbers for a project 200 years hence. Such a timber production system, however, is not new. There is a document indicating that during the Edo Period, the Iwakuni Domain planted trees for use in the Bridge. More recently, 2,000 zelkova trees were planted in 1991.

The tree-planting campaign for the Bridge has many purposes: preserving and passing down local traditional culture and technology, nourishing water sources, helping alleviate global warming, preserving biodiversity and developing a local culture of preserving the historic environment through Bridge rebuilding and tree planting on a regular basis.

Rebuilding Expenses

Since the Iwakuni Domain needed considerable funds to build and rebuild the Bridge in 1673 and 1674, respectively, the Domain ordered its vassals and merchants to share the expense. The share for vassals was determined in accordance with their positions; the share of merchants was based on their family businesses. This system continued until 1871. Over the subsequent 95 years, Bridge rebuilding and maintenance was funded by donations and taxes.

On April 1, 1966 Iwakuni City began collecting tolls from pedestrians who cross the Bridge. The project to rebuild the Bridge during the Heisei Period cost 2.6 billion yen. Of the amount, 2.2 billion yen was funded by the tolls, the remaining 0.4 billion yen by the national and prefectural governments. To maintain the Kintaikyo Bridge, the local authority will continue collecting tolls.